How was I supposed to know that when I moved to a foreign land called Oklahoma at age 11 I was actually returning as a 6th generation Oklahoman to a soil soaked with the blood, sweat and tears of my ancestors? No one ever told me.

How was I supposed to know that while working as a journalist in Tulsa, the lands of Eastern Oklahoma—on which my ancestors exercised their freedom from Cherokee Nation slavery— would become like a new world to me? No one ever told me.

Bartlesville, Nowata, Fort Gibson and Webber’s Falls. Lands touched, toiled and traversed by my direct line of ancestors. What once felt like blips barely registering on the radar of my awareness now hold astronomical significance to my ancestors’ origin story and to the story I hope to tell in the future.

Months into my Cherokee Freedmen ancestry journey, I feel like a veil has been lifted from my soul, as if there was a deep fog around my ancestral memory just beginning to clear.

Enslavement at Webber’s Falls

I am a descendant of Jim Foreman and Matilda Vann. Possessed like property by notorious and prominent Cherokee enslaver Joseph Vann, these 5x great-grandparents of mine joined their enslavers on the forced death march, known as the Trail of Tears in the 1830s, carrying their luggage.

A full 25 percent of the 20,000 who marched died, but my ancestors, despite carrying more on their shoulders, endured and survived. For their entire adult lives they continue their forced labor for the Vann Plantation at Webber’s Falls.

Emancipation at Fort Gibson

I am a descendant of Edmond Vann and Dinah Nave. Born into Cherokee Nation slavery, they gained their freedom after the Tribal nation passed a law emancipating enslaved people in 1863. With the signing of the Treaty of 1866, they became Cherokee Freedmen, guaranteed to enjoy the rights and citizenship of all Cherokee Nation citizens.

At a crowded government office at Fort Gibson, they would officially receive documentation guaranteeing their citizenship and identity as members of the Cherokee Nation, despite being segregated once again to the Cherokee Freedmen Dawes Roll.

Living on the land in Lenapah, Nowata

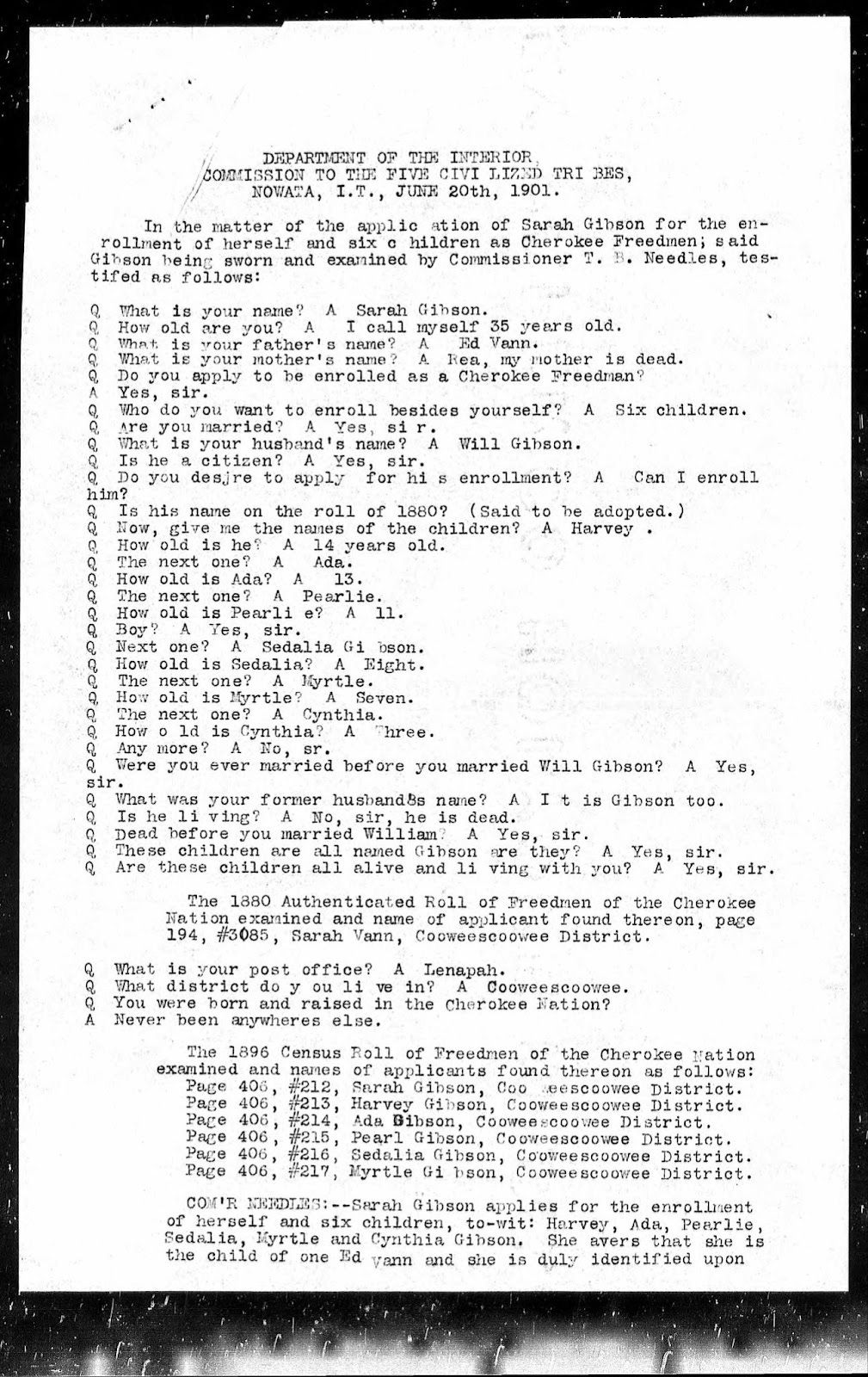

Making their way up to the old Coowescoowee Cherokee district, they lived their lives working the land as farmers in Lenapah. Their descendant Sarah Vann, and her husband William Gibson, would continue to live around the areas of Lenapah and Nowata, where my 2nd great grandmother Cynthia Lee Gibson lived her life.

The youngest of six children, I wouldn’t be alive if she hadn’t burst into the world. Records from the Cherokee Nation Freedmen Roll, despite its racist origins, prove the lineage of my family line.

My Granny’s fiery spirit

Twenty miles away, my granny Alma Lee Bryant Pettis (Now Alma Garrett), was born in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It was here where she would walk to the corner store with her friends and sometimes be lucky enough to get free candy and ice cream from the local business owners. A fiery spirit since birth, she would also ride the front of the segregated buses because “them white folks didn’t mess with me,” she once told me.

As a teenager with responsibilities no teenager should have to bear, she made her way to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where she eventually planted roots and gave birth to my father, uncles and aunt.

In her late 80s, she still has the same fiery spirit, but I don’t know for how much longer. With the time I have left, I’m determined to help her obtain her Cherokee Nation citizenship and plug in the holes missing from our family’s collective story.

Telling their story is my legacy and responsibility

My ancestors weren’t stationary. Their life was about movement and adapting to the land. Many of them didn’t stay in Oklahoma, migrating to the midwest and other parts of the United States in the early 20th century.

Yet, it’s the soil of Webber’s Falls, Fort Gibson, Bartlesville, Nowata, Lenapah, Cooweescoowee District, that continues to hold the imprint of their steps, the tears of their sorrows, the sounds of their laughter and the memory of their souls.

In a recent interview with Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. for my podcast In Depth With Deon, I asked him about his administration’s efforts to make amends and provide equity and reconciliation for the descendants of formerly enslaved Cherokee Freedmen.

We’ve got to “talk about programs and services, talk about something you’re dealing with now, which is ‘how do I take that path from my family story to documented ancestry, to a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. You’re on that journey right now. That’s a difficult journey for Freedmen descendants often because they’ve got to go back to the turn of the 20th Century. I didn’t have to do that,” Chief Hoskin Jr. told me.

“That's part of the effort is taking some affirmative steps, recognizing that a people who were suppressed for a century and a half cannot be expected to fully be able to exercise their rights as citizens, the opportunities that citizenship brings, and the obligations that citizenship brings, unless the government of the Cherokee Nation recognizes that one of the ways we reconcile is to go into communities and say how can we help,” Chief Hoskin Jr. said.

My family’s story stretches beyond the so-called “State of Oklahoma” back to the old Cherokee lands of North Georgia and South Tennessee, and even further back to the West African shores of present-day Benin.

As an activist, community advocate and journalist, I’d always known I’ve inherited my granny’s fiery spirit, but now I’m beginning to know why. My ancestors survived oceans of obstacles. Yet, they endured. I’m here to continue their legacy, obtain citizenship for my family and write a new chapter.

Thank you for joining me on this journey.

Share this post